Quick Results with AI-Assisted Coding – What Changed in the Past 2,5 Years?

The promise of AI in software development is often sold as a magic button—instant applications and zero friction. But what happens when you actually try to build something from scratch? To test the limits of AI-assisted coding, I built a video game with my son. Here’s the documentation of the journey, key takeaways and the playable demo itself – enjoy!

Juho Jutila

Juho is a Business Architect with over 20 years of experience in building competitive strategies and leveraging both emerging and proven technologies to help global organisations succeed. Before Vuono Group, he worked as a consultant at Accenture, Columbia Road and Futurice, to name a few.

Experimenting with AI-assisted coding: building a video game

A couple of years ago, I published a blog post about experimenting with code generation with ChatGPT. The project scope was very limited, the approach was more like a crude hack, and it was for my personal use. I learnt a lot, and the process opened new doors for me. I was no longer just talking about things; I could actually do them.

Code generation became topical again a few weeks ago. I have been looking for projects to do together with my younger son. We’ve been focusing on video production, but so far he has shown little interest in actual software development. Recently, I had some adventures with smartphone device security. Think about the tenacity of a pre-teenager trying to circumvent the usage restrictions set by his parents. Ok, the kid’s not stupid. He’s actually pretty good with computers. Fine. Information system security is pretty important, but let’s find something else to do.

Not so surprisingly, he likes to spend time gaming. While that is not all bad, spending too much time on it can be counterproductive. I’ve been eyeballing different JavaScript presentation frameworks now and then. Why not do something even more interactive with the possibility to use your own artwork and sounds? Why don’t we make a skateboarding game of our own?

Experimentations with sprite generation:

Bigger context windows mean that AI can handle bigger chunks of code

2,5 years ago, I had to break my code into tiny fragments. The more code I pasted into an editor, the more likely it was going to break. I really needed to work with snippets, and it restricted the scope significantly. I didn’t use version control (a big mistake) since it was just a small experiment, and relied on commenting out previous versions in the source. Currently, I can generate entire modules of hundreds of lines. It works surprisingly well. For my own learning, I did generate individual functions along the way. A big asset was that I could modify code without resorting completely to AI.

No, I do not have the patience to build everything from the ground up with a coding copilot. My approach is top-down. I ask: What is the biggest unit of analysis I can use to deal with a problem? And don’t get me wrong, I am fine to dive into the details. It should be fine-tuning rather than creating new functionality or major reorganisation of code. I divided the player controls and the different stages into separate files. And no, not everything worked like a charm.

AI can discuss organising the code. It helped me understand how different pieces are connected and address my concerns. On the other hand, give it bad guidance, and it will walk you through the exact steps needed to make overcooked spaghetti.

Next time I’ll be able to ask more of the right questions, and no doubt discover new ways to mess things up. Changing things afterwards has also proven difficult. Splitting a file into several separate ones is better done by hand. Sure, AI does it for you, but it might forget to include some of the graphics or lose the soundtrack in the process. Better not be too ambitious with the refactoring and restructuring.

“AI can discuss organising the code. It helped me understand how different pieces are connected and address my concerns.”

And don’t get me wrong. The process was breathtaking in many ways. I selected an available code framework suitable for our purposes, set up local version control, created a functional starting point with a rectangle I could control with the arrow keys, and a collectable rectangle of another colour that increased the point count.

I think it’s the adage of AI-fueled software development of our age. You can get impressive initial returns pronto. Also, I bet the teaching material is full of code that produces rudimentary starting points for projects like this. The real work begins when you start extending it and must apply systems-thinking principles to keep it from falling apart. Sure, the game can have a sloppy vibe (pun intended), but it should still be smooth.

“The real work begins when you start extending it and must apply systems-thinking principles to keep it from falling apart.”

The infamous automated trash

I heard a client revisit the old proverb: “If you automate trash with AI, you’ll get a dumpster fire”. I am so glad I can isolate my experiments. Let me illustrate how AI thinks through a couple of examples.

The physics dilemma: arcade vs. matter

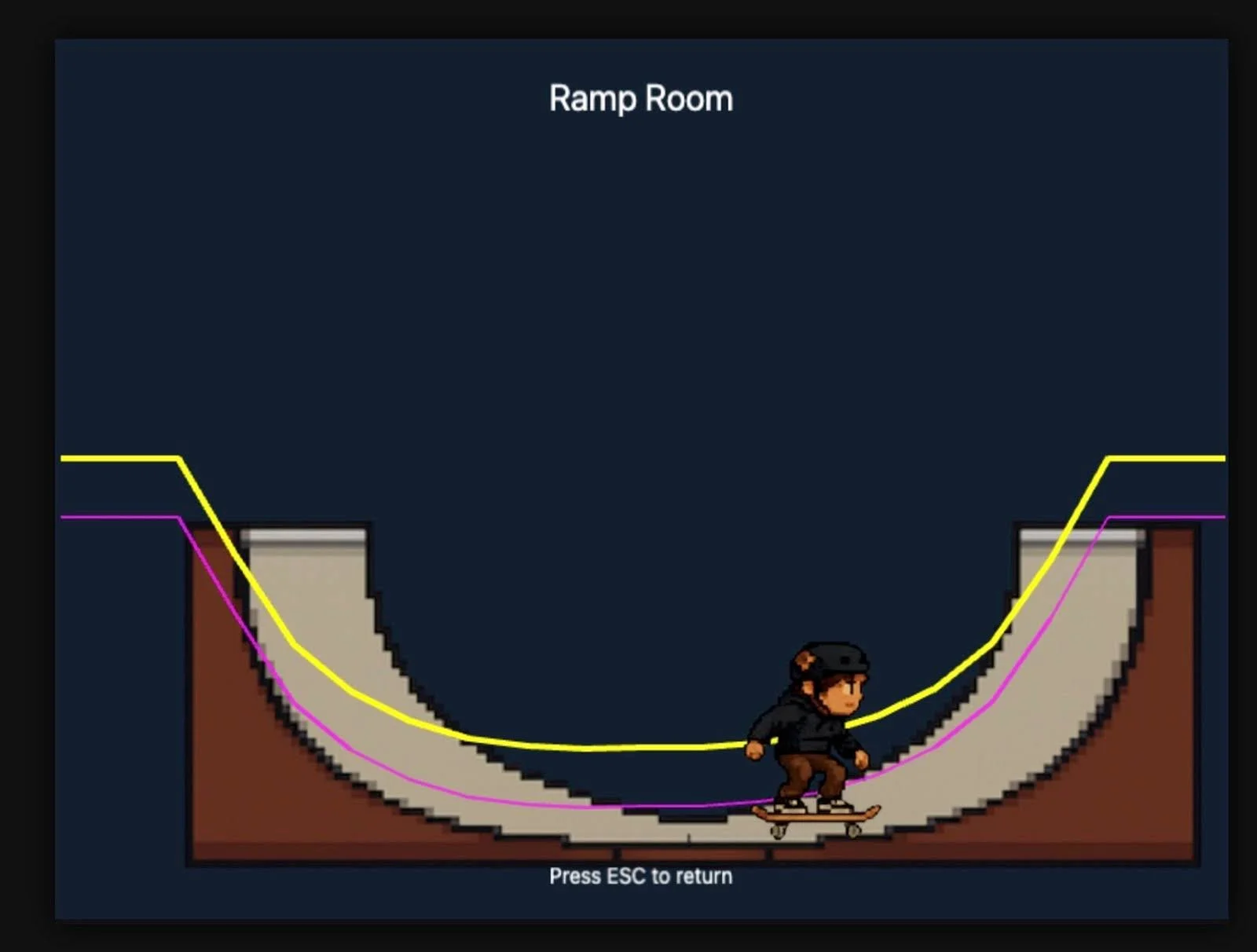

The initial physics model worked great! I learnt that the framework we use offers two kinds of models: arcade and matter. Arcade is more game-like and offers a straightforward way to create objects you can bounce against. Matter is closer to actual physics and allows the creation of arbitrary splines that define the physical boundaries of the game world. The initial code came with the arcade model. For skateboarding, the matter model might be nicer to have, since skateboarding is a lot about rolling on curved surfaces.

I had generated a nice-looking pixel-art half-pipe ramp, and I wanted to create a ramp scene. I imagined the skater moving along the spline, tracing the ramp’s shape. Unfortunately, AI had scaled the player sprite a bit to make it look nicer. I did scale him down anyway from 1536x1024 and did some cropping, but why not adjust his size in code? Also, the ramp elements were scaled to fit the screen for nice positioning. Again, first with image processing, but then fine-tuning with the code.

Mapping coordinates and other issues along the way

The simple matter of mapping the spline coordinates to the ramp proved far from simple. The ramp and the player had different scaling factors. In addition, despite asking nicely (and ultimately not so nicely) to use absolute values in coordinate pairs, it was mission impossible for AI. It confirmed my request but kept generating spline definitions that included not only numbers but also variables such as height and width. I understand that’s how you make liquid layouts and that the teaching material is full of that, but how hard can it be?

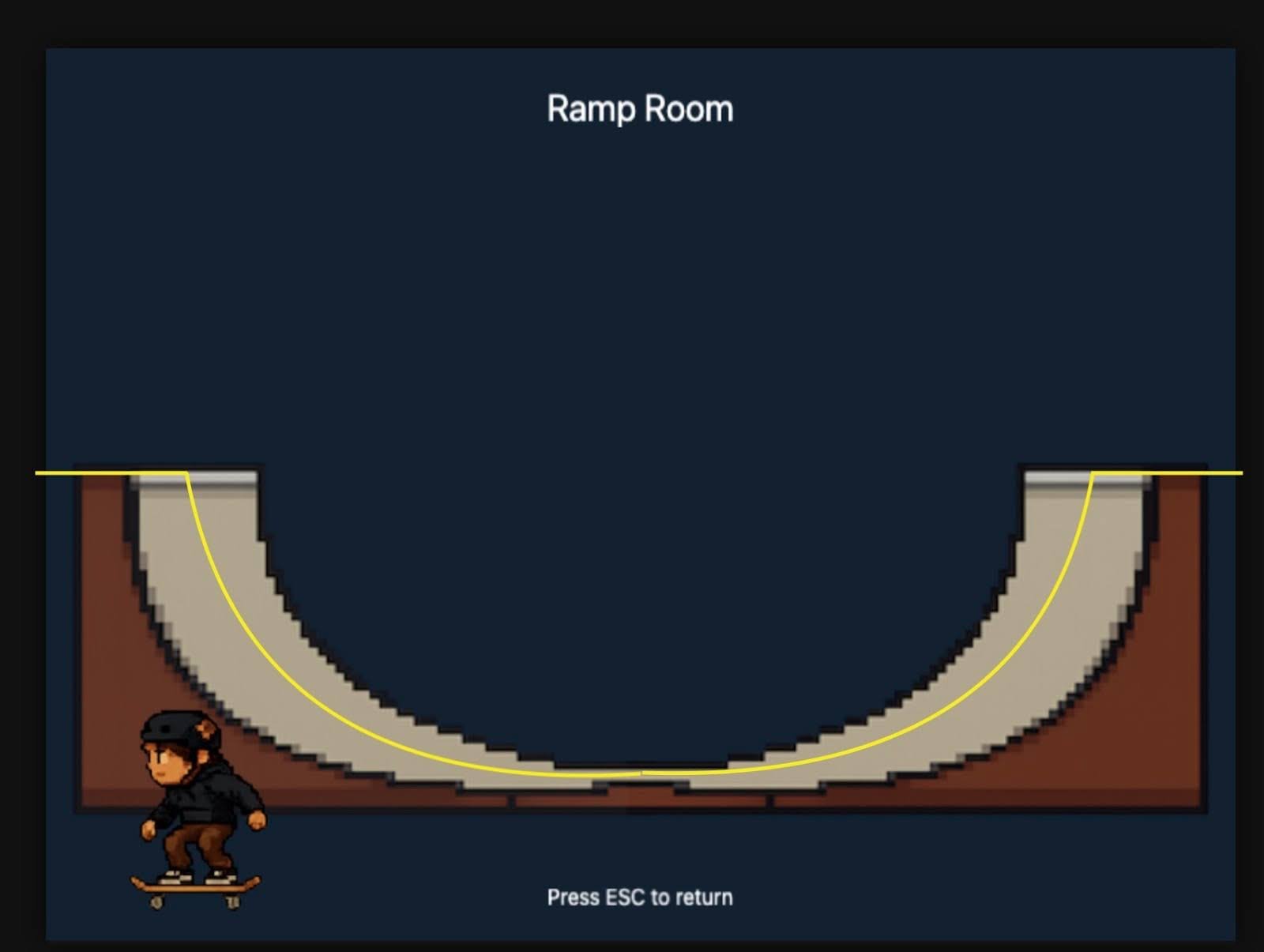

Debugging the spline definitions was extremely frustrating. The spline was invisible on the screen. I had to ask for the code to paint the spline in question bright yellow. I ended up with a game that had a nice ramp, a player moving along an invisible ramp, and a yellow debug line that didn’t match either the ramp or the player’s trajectory. After further investigation, AI had generated code that used a completely separate set of coordinates to plot the debug line. Sometimes it feels like common sense is a superpower. Talking about dumpster fires…

And using different physics models for the main scene and the ramp scene? That’s a great idea! I had to make multiple iterations before the AI realised that, within the framework I was using, it was not practical at all. The amount of boilerplate code needed for that would have far exceeded the actual game logic code, with a multiplier.

The plan and the vibey reality:

A trivial migration from arcade physics to matter-based physics for a codebase less than 600 rows (including comments) proved to be not so trivial. And don’t get me started on setting the ground level. If a human developer told me time after time how great my bug report was, that’s exactly the info they needed to fix the problem, and still provided the same code as before, I’d be like, “Dude, you are getting some kind of help, I hope?”

A bit of manual coding to get the demo working

I ended up modifying the spline-defining matrix by hand. When it was close enough, I called it a day. There was little point in prolonging the game. The codebase was too big and tangled. I could just add more music, throw in some background graphics, and push out a demo. I learnt so much that it’s better to start the project basically from scratch. Despite the technical headaches with physics, the ability to simply create remains the most powerful aspect of this technology and project.

A game that has some rock’n’roll in it

I spend most of my working hours with software developers and architects. I represent them, advocate their viewpoints, help them resolve blockers, and let them point me towards the stakeholders they find troublesome. I create a lot of documentation, from concept design to actual functional specifications and detailed data models. I have utmost respect for technical competence and appreciate a good developer.

I think and talk a lot about technology, but rarely get to touch actual code or configuration files. AI has changed that for me. I can do my thing, but then dip my toes into actually building things. My technical education has been outdated for more than a decade, and the barrier to getting back into the game has been way too high. Now, thanks to AI, I can jump back on the saddle and actually deploy things. I wouldn’t build anything too critical, but hey, an interactive toy that explores game development is just the ticket.

Interactive graphics, sound effects, physics models, and a playable demo? It feels pretty cool when you think about it. It’s something I could not have done with reasonable effort some time ago.

Involving my kid in the development process has been both beneficial and fun. We took a photo of him dropping with a skateboard, and generated a pixelated player sprite from that. We generated additional sprites from that: the player jumping, kicking speed, and braking with the skateboard. It was relatively easy to implement sprite animation logic into the game.

There’s another feature of current AI tools: they tend to nail part of the problem, but struggle to deliver the whole. While ChatGPT’s Dall-E does great work with images, it was not able to consistently generate player sprites. Gemini’s Nano Banana Pro is very consistent, but it couldn’t generate images with transparent backgrounds. Gemini sure did generate the gray-white grid representing transparency, but not actual transparent images. ChatGPT’s image generator couldn’t keep the skin tone consistent, and the player's different pants while jumping were not very convenient.

“AI tools tend to nail part of the problem, but struggle to deliver the whole.”

We had to use both generators and some image processing to create output that was good enough. No tool was a silver bullet, and we had to patch the outputs into a workflow that produced consistent outputs. If you look more closely at the pixel art, the individual pixels show AI artefacts at the edges. It’s not actually pixelated, but screams “synthetic”. On the other hand, it gives an indie-like look and feel that isn’t overly polished. The player sprite graphics carry some of our attitude when we horse around in an actual skatepark with our crew. It’s undisciplined, raw, and playful energy, yet somehow impressive. Be the judge of this mental gymnastics, try the game demo, and consider how it looks and feels.

In any case, showing the kid how the sprite animation is made and adjusted was great. He had a ton of ideas on additional sprites we could use. He showed interest in image processing, something I can teach him.

Any respectable game needs a legendary soundtrack, right? Kid’s been experimenting with a MIDI keyboard and GarageBand for his YouTube videos. He composed the music for the first scene, and I was able to loop it in the background. And my talented brother was kind enough to create the background music for the ramp scene. It’s not too polished, but it fits the game vibe nicely. I did some experimentation with AI-generated music, but it lacked... well, soul?

It’s been great to involve my kid in the concept design and testing. He also has many ideas for further development. We will surely take them beyond just this demo. My colleagues were quite helpful in the transition to GitHub. They have given encouraging comments like: “I’ve played games that have been done with considerably bigger resources and are less enjoyable experiences”. Not bad for a demo.

My verdict: towards software at the speed of thought

When I started my career in tech, huge teams were building services with a much narrower scope than today. Today, a small, skilful team can deliver a lot. Tools have improved, there’s so much more available, and the entire industry has matured during that time. At the same time, there are many more software engineers, and their skill sets and levels are far more varied. AI-assisted software is the next step along that continuum. We will see a lot more software in the foreseeable future.

As a consequence, the quality of this software will vary. As volume grows, we will also see more issues with user experience, resource usage, and security. The term “AI slop” exists for a reason. Systems thinking and product mindset matter now more than ever. Soon, we will be able to turn a business strategy into working software with the push of a button. At the same time, it’s kinda exciting and kinda horrifying.

Key takeaways for AI-assisted coding in business:

Architectural oversight is non-negotiable: AI acts as a powerful force multiplier for writing code, but it lacks the "big picture" view. Without a human applying systems thinking and top-down architectural guidance, AI tools can quickly generate unmanageable "spaghetti code."

The "reviewer" role is replacing the "writer" role: As generation becomes easier, the bottleneck shifts to verification. Debugging AI-generated logic requires a different skillset—one focused on logic, integration, and spotting subtle hallucinations—rather than just syntax memory.

Rapid prototyping vs. production quality: AI excels at getting a project from zero to one (the "demo" phase). However, extending that codebase requires significant refactoring. For business cases, this means faster Proof-of-Concepts (PoCs), but potentially higher technical debt if the initial AI code isn’t rigorously managed.

Democratisation of development: Large context windows now allow functional experts (like architects or product owners) to contribute directly to the codebase. This blurs the lines between technical specification and implementation, potentially accelerating the "Concept-to-Code" pipeline.

Now, take a ride on the skateboard and try the demo for yourself – just click it to activate the controls and enjoy! And sorry, desktops only.

In case you need a direct link: https://juhokawaii.github.io/Skate-Hustle-Demo/